What financial institutions need to know about the rise of digital lending

By Justin Schray; Credit Analyst, Young & Associates

Visiting a local bank or credit union isn’t always practical anymore. Mobile and digital lending platforms are reshaping financial services, giving consumers faster, more convenient and accessible options. Fintech leaders like SoFi, PayPal and Kabbage are driving this shift, using technology to meet borrowers’ changing needs.

One of the most significant advantages of mobile and digital lending is convenience. These platforms allow users to apply for loans, transfer funds and communicate with customer service representatives — all from the comfort of their home or while on the go. The digital loan application process is typically much faster than traditional methods, often delivering approvals within minutes. Furthermore, all necessary documentation is stored securely online, reducing the need for physical paperwork and enabling borrowers to access their information at any time.

Digital lending platforms also offer a wider range of services and investment opportunities. For example, many now provide “buy now, pay later” options, which are particularly popular among consumers making discretionary purchases, such as during vacations or seasonal shopping. Platforms like Kiva focus on providing microloans to entrepreneurs and small businesses, supporting underserved markets and fostering economic growth. This diversity in offerings ensures that digital lending can cater to a variety of financial needs and consumer preferences.

How financial institutions can compete and adapt to digital lending

To remain competitive in this evolving landscape, traditional financial institutions must invest in digital transformation initiatives that align with both consumer expectations and regulatory frameworks. While fintech’s have led the charge in agility and innovation, banks and credit unions can leverage their established reputations, trust and infrastructure to deliver equally compelling digital lending experiences.

Key steps institutions should take include:

- Invest in digital infrastructure: Banks must adopt modern loan origination systems (LOS), mobile banking platforms and secure cloud-based storage to replicate the speed and accessibility offered by fintechs.

- Partner with fintech providers: Collaborations with third-party technology vendors can accelerate the rollout of digital lending capabilities. Many vendors offer white-label or integrated solutions that align with the institution’s branding and compliance requirements.

- Enhance user experience: Developing intuitive user interfaces and streamlined applications is essential. Borrowers expect minimal friction, clear disclosures and mobile responsiveness throughout the lending process.

- Implement robust data analytics: Leveraging data to enhance underwriting, detect fraud and personalize lending solutions gives traditional institutions a competitive edge. Automation tools and AI-based decision-making can further improve efficiency.

- Staff training and change management: Internal teams should be trained not only on new systems but also on the institution’s digital strategy and compliance responsibilities. Change management efforts are critical to ensuring organization-wide adoption.

Maintaining regulatory compliance with digital lending

Rolling out digital lending solutions requires strict adherence to consumer protection regulations, data privacy laws and industry best practices.

Institutions must:

- Comply with lending regulations: Ensure all Truth in Lending Act (TILA), Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA) and Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) disclosures are digitally available and easily understood by consumers.

- Protect customer data: Maintain robust cybersecurity and encryption protocols to safeguard personally identifiable information (PII) in compliance with the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) and other relevant laws.

- Establish vendor due diligence programs: When working with third-party vendors, institutions must perform proper risk assessments, monitor ongoing performance and establish clear service-level agreements.

- Maintain audit trails and documentation: Regulators expect comprehensive documentation of loan decisions, disclosures and communications. Digital systems should be configured to automatically store and organize these records.

By investing in the right technologies, developing a thoughtful rollout plan and embedding regulatory compliance into each phase, financial institutions can successfully transition into the digital lending space and offer competitive alternatives to fintech challengers.

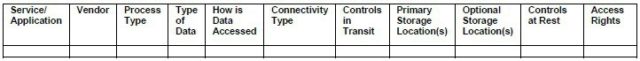

Here’s a way this could be used to illustrate the way that an institution can document data flow and data storage. You will first identify each Service or Application that uses NPI. Some examples of these services and applications include: core processing, lending platform, internet banking, and online loan applications. Next, you will identify the Vendor(s) associated with each service or application. The Process Type is used to identify the various processes that are performed using the specific service or application that may use different methods for accessing the data or result in data being transmitted through different connectivity types. An example of different process types can be illustrated with internet banking where data may flow between the core processing system and the internet banking system through a dedicated circuit, but customers access the internet banking system through a home internet connection. The Type of Data will most often be customer NPI, but may also include proprietary institution data. Data can be accessed in numerous ways including: institution workstations, institution servers, employee mobile devices, customer PCs, and customer mobile devices. The Connectivity Type may include: dedicated circuits, virtual private networks (VPN), local area networks (LAN), wide area networks (WAN), wireless networks, or the internet. Controls in Transit may include: encryption, firewall rules, patch management, and intrusion prevention systems (IPS). The Primary Storage Location(s) should include known locations where the data is stored such as: application or database servers, data backup devices, service provider datacenters, and service provider backup locations. The Optional Storage Location(s) should consider other places where data can be stored such as: removable media, an employee’s workstation, mobile devices, Dropbox, and Google Drive. Identifying the Optional Storage Location(s) may take a significant amount of time, as this step will involve discussions with application administrators to understand the options for exporting data and discussions with employees to understand their processes for transferring and storing data. A review of this information may lead to the implementation of additional controls to block the use of unapproved sharing and storage services.

Here’s a way this could be used to illustrate the way that an institution can document data flow and data storage. You will first identify each Service or Application that uses NPI. Some examples of these services and applications include: core processing, lending platform, internet banking, and online loan applications. Next, you will identify the Vendor(s) associated with each service or application. The Process Type is used to identify the various processes that are performed using the specific service or application that may use different methods for accessing the data or result in data being transmitted through different connectivity types. An example of different process types can be illustrated with internet banking where data may flow between the core processing system and the internet banking system through a dedicated circuit, but customers access the internet banking system through a home internet connection. The Type of Data will most often be customer NPI, but may also include proprietary institution data. Data can be accessed in numerous ways including: institution workstations, institution servers, employee mobile devices, customer PCs, and customer mobile devices. The Connectivity Type may include: dedicated circuits, virtual private networks (VPN), local area networks (LAN), wide area networks (WAN), wireless networks, or the internet. Controls in Transit may include: encryption, firewall rules, patch management, and intrusion prevention systems (IPS). The Primary Storage Location(s) should include known locations where the data is stored such as: application or database servers, data backup devices, service provider datacenters, and service provider backup locations. The Optional Storage Location(s) should consider other places where data can be stored such as: removable media, an employee’s workstation, mobile devices, Dropbox, and Google Drive. Identifying the Optional Storage Location(s) may take a significant amount of time, as this step will involve discussions with application administrators to understand the options for exporting data and discussions with employees to understand their processes for transferring and storing data. A review of this information may lead to the implementation of additional controls to block the use of unapproved sharing and storage services.