- The OCC’s Semiannual Risk Perspective for Spring 2015, published June 30, 2015, shows that 30+-day delinquency rates for loans that have reached end-of-draw at the nine largest OCC-regulated banks have essentially doubled in the three-months following the end of the draw period, and have remained persistently high. The OCC also notes that, “many lenders have found the early stages more challenging than expected,” which should provide a wake-up call for any banks that still believe this issue will take care of itself without proactive management on the part of the bank.

- Data provided by Equifax, which was cited in a front-page Wall Street Journal article in June, indicated that just four months after reaching the end-of-draw period, HELOC borrowers from the 2004 vintage saw 30+-day delinquency rates increase by over 50% from the month prior to when they reached end-of-draw (2.7% to 4.3%). Similar increases are shown for vintages from 2000-2003 as well.

- A study by Experian, reported on its website, showed that 90-day delinquency rates increased three-fold during the 12 months of 2014 for those borrowers that reached their end-of-draw period between December 2013 and March 2014.

- Research published in the May 2015 RMA Journal by the other primary credit reporting agency, TransUnion, does not provide as directly comparable data as the previously mentioned studies, but does indicate that its data set of HELOCs showed overall 30+-day delinquencies of 2.2% while HELOCs 12 months after their payment shock showed a 60+-day delinquency rate of 3.1%.

The overall takeaway from all of this data is that the intuitive and expected impact of HELOC payment shock—increases in delinquency and eventually default and loss rates—does in fact appear to be occurring.

Impact on Community Banks and Risk Management Steps

The experience of any individual community bank will by no means mirror the overall industry experience. For one thing, the minimum payment required during the draw period does vary across banks, and banks that require significant principal reduction each month during the draw period may be less vulnerable to payment shock than those that required just interest-only payments. (Requiring principal reduction during the draw period certainly does not make a bank immune from payment shock, as it is important to keep in mind that the borrower also loses access to the line of credit as a source of funds when the draw period ends.) Further, community banks may have some advantages over larger lenders in terms of customer familiarity that may assist in working through end-of-draw issues with borrowers.

With that said, it is important to recognize that both the theory and the data are in line on this issue so far: all else equal, payment shock results in increased risk for the lender. In fact, the credit reporting agency research cited above also provides data indicating that the negative effects of payment shocks carry over to other credit facilities of borrowers, which presents an additional source of risk to relationship-minded community banks who may have multiple loans with a HELOC borrower. For these reasons, it is important that all community banks with HELOC exposures evaluate the interagency guidance’s recommendations and take the actions appropriate for their portfolio. We discussed these issues in more detail last year, but important steps include: 1) defining consistent and prudent options for borrowers approaching the end of their draw period that take into account the borrowers’ current financial and home value positions; 2) proactively initiating contact with borrowers who are approaching the end of their draw periods; 3) ensuring that all relevant parties within the bank have a voice in the bank’s approach to mitigating risk and are well-versed in the steps to follow with end-of-draw borrowers; and 4) gathering and analyzing enough data specific to your bank to fully understand the nature of the risk your bank faces.

End-of-draw risk does not need to lead to a massive amount of charge-offs to materially impact a community bank’s performance, especially given the low level of charge-offs many banks have been experiencing in that portfolio. Though there are very few, if any, banks for which end-of-draw concerns may represent an existential risk, a failure to properly manage end-of-draw risk could easily have a notable impact on earnings over the next several years, and could also result in weak regulatory assessments of a bank’s risk management. The OCC has publicly noted that it is pursuing a review of HELOC practices, and while this targeted horizontal review is unlikely to directly affect community banks, it would be a good bet that HELOC end-of-draw practices will be a point of emphasis in many community banks’ next safety and soundness exam, regardless of the examining agency.

Conclusion

The evidence continues to suggest that proper risk management of end-of-draw HELOCs is important. One consideration not directly mentioned above is that some banks may also find it beneficial to use their end-of-draw experience to consider whether any changes to their existing HELOC product’s structure would be appropriate. If you have questions or would like to discuss your end-of-draw risk management, please contact me at ttroyer@younginc.com or 1.800.525.9775.

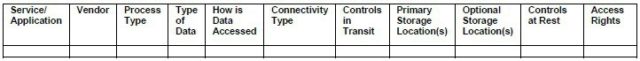

Here’s a way this could be used to illustrate the way that an institution can document data flow and data storage. You will first identify each Service or Application that uses NPI. Some examples of these services and applications include: core processing, lending platform, internet banking, and online loan applications. Next, you will identify the Vendor(s) associated with each service or application. The Process Type is used to identify the various processes that are performed using the specific service or application that may use different methods for accessing the data or result in data being transmitted through different connectivity types. An example of different process types can be illustrated with internet banking where data may flow between the core processing system and the internet banking system through a dedicated circuit, but customers access the internet banking system through a home internet connection. The Type of Data will most often be customer NPI, but may also include proprietary institution data. Data can be accessed in numerous ways including: institution workstations, institution servers, employee mobile devices, customer PCs, and customer mobile devices. The Connectivity Type may include: dedicated circuits, virtual private networks (VPN), local area networks (LAN), wide area networks (WAN), wireless networks, or the internet. Controls in Transit may include: encryption, firewall rules, patch management, and intrusion prevention systems (IPS). The Primary Storage Location(s) should include known locations where the data is stored such as: application or database servers, data backup devices, service provider datacenters, and service provider backup locations. The Optional Storage Location(s) should consider other places where data can be stored such as: removable media, an employee’s workstation, mobile devices, Dropbox, and Google Drive. Identifying the Optional Storage Location(s) may take a significant amount of time, as this step will involve discussions with application administrators to understand the options for exporting data and discussions with employees to understand their processes for transferring and storing data. A review of this information may lead to the implementation of additional controls to block the use of unapproved sharing and storage services.

Here’s a way this could be used to illustrate the way that an institution can document data flow and data storage. You will first identify each Service or Application that uses NPI. Some examples of these services and applications include: core processing, lending platform, internet banking, and online loan applications. Next, you will identify the Vendor(s) associated with each service or application. The Process Type is used to identify the various processes that are performed using the specific service or application that may use different methods for accessing the data or result in data being transmitted through different connectivity types. An example of different process types can be illustrated with internet banking where data may flow between the core processing system and the internet banking system through a dedicated circuit, but customers access the internet banking system through a home internet connection. The Type of Data will most often be customer NPI, but may also include proprietary institution data. Data can be accessed in numerous ways including: institution workstations, institution servers, employee mobile devices, customer PCs, and customer mobile devices. The Connectivity Type may include: dedicated circuits, virtual private networks (VPN), local area networks (LAN), wide area networks (WAN), wireless networks, or the internet. Controls in Transit may include: encryption, firewall rules, patch management, and intrusion prevention systems (IPS). The Primary Storage Location(s) should include known locations where the data is stored such as: application or database servers, data backup devices, service provider datacenters, and service provider backup locations. The Optional Storage Location(s) should consider other places where data can be stored such as: removable media, an employee’s workstation, mobile devices, Dropbox, and Google Drive. Identifying the Optional Storage Location(s) may take a significant amount of time, as this step will involve discussions with application administrators to understand the options for exporting data and discussions with employees to understand their processes for transferring and storing data. A review of this information may lead to the implementation of additional controls to block the use of unapproved sharing and storage services.

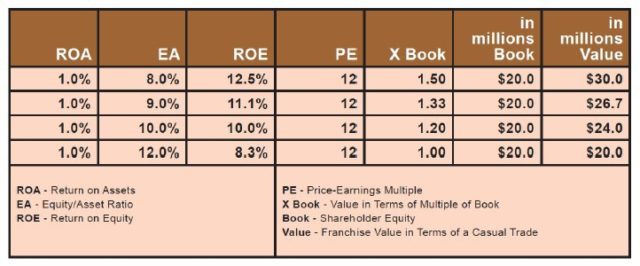

Another example of the cost of excess capital can be seen here. There are four banks with a 1% ROA. However, the equity/asset ratio at each is different, ranging from an 8.0% leverage ratio to a 12.0% leverage ratio. By dividing the ROA by the leverage ratio, you get the ROE. By multiplying the ROE by an assumed PE, you get the multiple of book. In this example, the bank with an 8.0% leverage ratio has a value of $30 million while the bank with a 12.0% leverage ratio has a value of $20 million. This is a simplified example that provides information on the cost of excess capital.

Another example of the cost of excess capital can be seen here. There are four banks with a 1% ROA. However, the equity/asset ratio at each is different, ranging from an 8.0% leverage ratio to a 12.0% leverage ratio. By dividing the ROA by the leverage ratio, you get the ROE. By multiplying the ROE by an assumed PE, you get the multiple of book. In this example, the bank with an 8.0% leverage ratio has a value of $30 million while the bank with a 12.0% leverage ratio has a value of $20 million. This is a simplified example that provides information on the cost of excess capital.